The story behind my first contribution to the Linux kernel

Attention: this is not a tutorial. This post combines technical approach and personal narrative. Steps like QEMU setup, debostrapping and kernel compiling are not being covered here. For this I suggest this excellent article from Javier Carrasco Cruz.

Prologue

Although I have been working in web development for the past six years and understand its challenges, I never found it particularly playful—please don’t misunderstand me, web colleagues; it’s simply a matter of personal preference. My true passions in computing have always been programming and operating systems—especially UNIX-based ones—and I have long been obsessed with the idea of uniting these two realms, whether professionally or as a hobby. I also love hardware, even though my knowledge of electronics is very limited.

As a Linux user and enthusiast for 12 years, I have always seen the Linux kernel as a project that synthesizes all of these passions together. However, finding an entry point to study it—and the time to do so—was always a challenge. Given its niche nature, it took me a long time before I encountered people and study groups with similar interests… but that goal never left my mind.

Diving deeper into web development and decoupled code architectures, however, provided me with the foundation to begin understanding the various abstraction layers of the kernel and how they connect with one another—for instance, the relationship between the VFS (Virtual File System) and concrete file systems like Ext4 and Btrfs.

It has been a long, somewhat solitary, and challenging journey to reach this milestone: my first contribution to the world’s largest open source project.

Special thanks

I would like to express my gratitude to the folks at FLUSP from the University of São Paulo, who welcomed me into their Linux kernel development workshop. I had the opportunity to meet these inspiring people only after moving to São Paulo, near USP, where we have the CCSL, the Free Software Competence Center.

Through FLUSP, I was introduced to the LKCAMP community - an equivalent study group at the University of Campinas (Unicamp). In their workshop, I learned the contribution process and gained invaluable experience in debugging the kernel.

Syzbot

The most practical way to find bugs in the Linux kernel is through Syzbot. Syzbot emerged as part of the syzkaller project, a fuzzer developed by Google to find bugs in the Linux kernel and other operating systems. The syzkaller was first developed by Dmitry Vyukov, a software engineer at Google, and was designed to automatically generate and execute random system calls (syscalls) with the aim of identifying flaws such as use-after-free, out-of-bounds access and data races.

The bug

First, let’s analyze the top of the stack trace provided by the crash report of the bug, I chose, highlighting the lines that matter most:

...

Call Trace:

<TASK>

__dump_stack lib/dump_stack.c:94 [inline]

dump_stack_lvl+0x116/0x1f0 lib/dump_stack.c:120

print_address_description mm/kasan/report.c:378 [inline]

print_report+0xc3/0x620 mm/kasan/report.c:489

kasan_report+0xd9/0x110 mm/kasan/report.c:602

usb_check_int_endpoints+0x247/0x270 drivers/usb/core/usb.c:277 <---

thrustmaster_interrupts drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c:176 [inline] <---

thrustmaster_probe drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c:347 [inline]

thrustmaster_probe+0x499/0xe10 drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c:289

__hid_device_probe drivers/hid/hid-core.c:2713 [inline]

hid_device_probe+0x349/0x700 drivers/hid/hid-core.c:2750

...

</TASK>

...

Syzkaller encountered a stack-out-of-bounds read in the driver module for Thrustmaster joysticks. A stack-out-of-bounds read occurs when a program tries to access memory outside the allocated stack range.

1. The reproducer program

The syzkaller may or may not generate a reproducer program for a bug, provided as a C source file (repro.c). Whether a reproducer program is generated depends on the nature of the bug. If all the reproduction conditions are clear and can be tracked by the fuzzer - allowing a well-defined reproduction path - the syzkaller system will generate a repro.c file for that bug.

In some cases, however, things are less straightforward. Certain bugs arise in non-deterministic scenarios, such as specific memory states, race conditions, uninitialized memory, or heap corruptions. In these cases, a simple syscall sequence might not be enough to trigger the issue consistently.

Fortunately, that wasn’t the case here. This bug can easily be triggered through its repro program. Instead of showing you a print from my machine, You can see the entire crash through the crash log from the bug provided by Syzbot.

2. Analysis

In fact, the problematic code was not in the core USB driver itself, but in drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c, the HID (Human Interface Device) driver for Thrustmaster joysticks. Essentially, an HID driver is responsible for handling input from devices — such as keyboards, mice, and joysticks — by interpreting raw hardware signals and converting them into standardized events that the operating system can process.

At a certain point, the HID driver code calls the usb_check_int_endpoints function from drivers/usb/core/usb.c within the USB subsystem, passing it the ep_addr array, which contains a single USB endpoint. USB endpoints are communication channels on a USB device through which data is transferred between the host and the device. They are characterized by their direction (IN/OUT) and type (e.g., control, bulk, interrupt, or isochronous). The role of this function is to validate the array of endpoints, ensuring that each endpoint is correctly configured for interrupt transfers. By the way, here’s a good example of how the subsystems talk to each other.

// drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c

...

ep = &usbif->cur_altsetting->endpoint[1];

b_ep = ep->desc.bEndpointAddress;

u8 ep_addr[1] = {b_ep};

if (!usb_check_int_endpoints(usbif, ep_addr)) {

hid_err(hdev, "Unexpected non-int endpoint\n");

return;

}

...

The issue is that usb_check_int_endpoints iterates over the passed array using a for loop to process each element, leading to a kernel panic.

// drivers/usb/core/usb.c

bool usb_check_int_endpoints(

const struct usb_interface *intf, const u8 *ep_addrs)

{

const struct usb_host_endpoint *ep;

// The for loop iterates to a next, non-existent element of ep_addrs

for (; *ep_addrs; ++ep_addrs) {

ep = usb_find_endpoint(intf, *ep_addrs);

if (!ep || !usb_endpoint_xfer_int(&ep->desc))

return false;

}

return true;

}

EXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL(usb_check_int_endpoints);

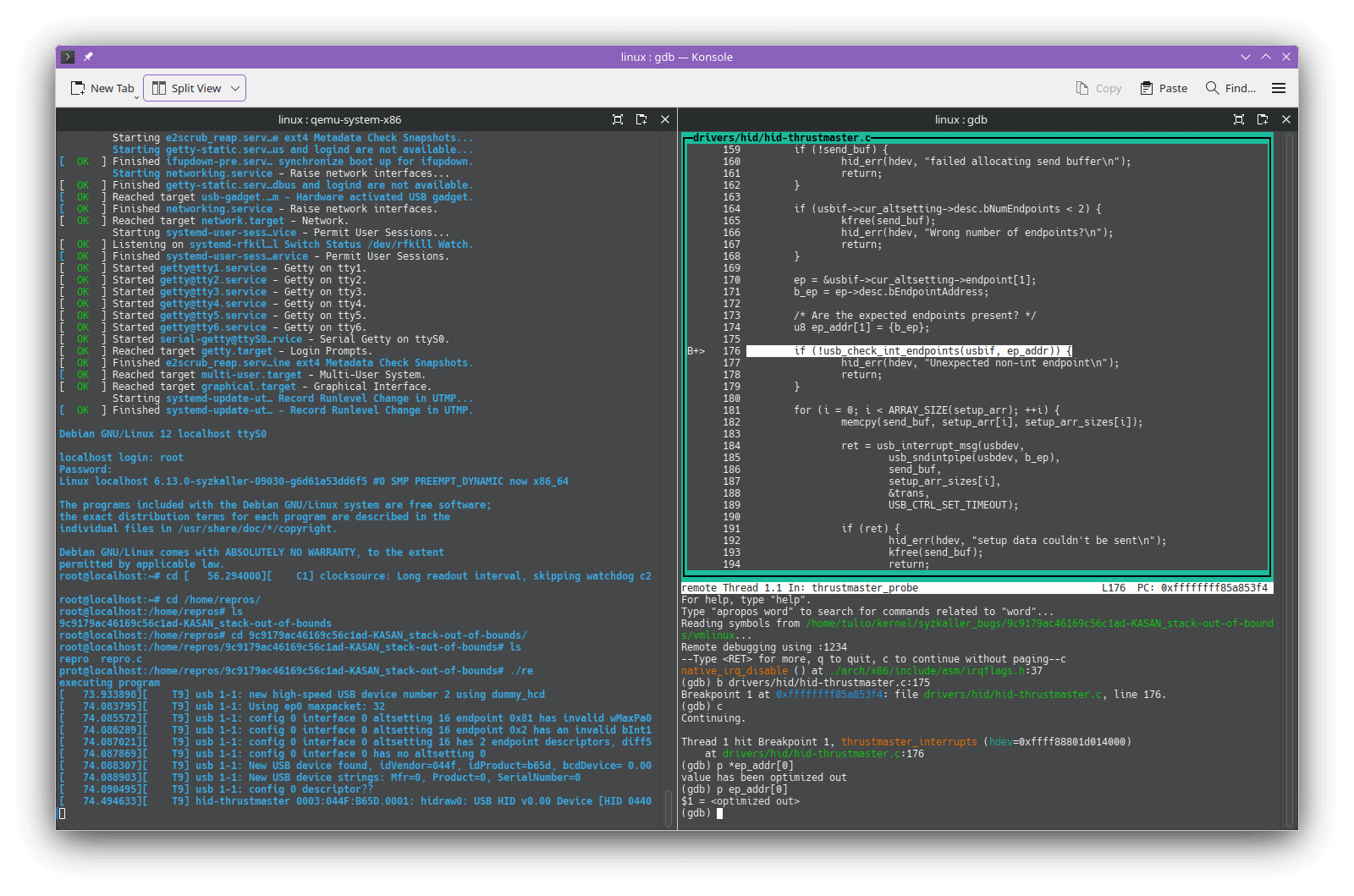

By debugging this through QEMU and gdb, I noticed that the sole element in ep_addr was not null:

So, what else could lead to a crash? After all, the array contains a valid element, right? Well…

First of all, please note that this is not a conventional for loop, as it does not use a dedicated counter variable like i to track the array size. Instead, it iterates by pre-incrementing directly over the elements of the passed array, whose size is unknown—remember, the USB subsystem doesn’t know in advance how many endpoints each USB device has, since its purpose is to be device-agnostic layer, and flexible enough to support a wide variety of endpoint configurations. Without a control variable, the loop can only determine when to stop iterating if it encounters a sentinel value—in this case, a null element—that represents the end of the array.

Considering the context of kernel software, where every byte matters, optimization and efficiency are critical. In the kernel context, even a minor overhead can be significant, which is why techniques such as using sentinel values instead of explicit counters are sometimes preferred. However, this approach relies on the array being properly terminated. If the sentinel value is missing, the loop will continue past the array’s bounds, leading to undefined behavior and, as observed here, a kernel crash.

3. The fix

As we saw, the problem was that the outer endpoint array did not contain a null terminating value. The solution I found was to simply null-terminate the array by adding an extra zero element.

// drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c

...

u8 ep_addr[2] = {b_ep, 0};

if (!usb_check_int_endpoints(usbif, ep_addr)) {

hid_err(hdev, "Unexpected non-int endpoint\n");

return;

}

...

This way, the for loop in usb.c correctly recognizes the end of the array, preventing it from iterating beyond its valid elements.

4. Testing

After applying my solution, I recompiled the kernel, booted it in QEMU, and executed the repro program again. Voilà: the kernel panic no longer occurred! You can check the logs directly from Syzbot.

In some cases, testing may require more thorough analysis than simply verifying that the repro program no longer crashes, but for this case, that was sufficient.

Submission process

1. Sending the patch

On February 5th, 2025, after applying and testing my solution, I generated a patch file using the git format-patch command, ensuring that the commit title and description were appropriately detailed and standardized.

From 6515fc6350d3997bc883c062aca3af2eecc93a12 Mon Sep 17 00:00:00 2001

From: =?UTF-8?q?T=C3=BAlio=20Fernandes?= <tulio@localhost.localdomain>

Date: Sun, 2 Feb 2025 21:58:30 -0300

Subject: [PATCH] HID: hid-thrustmaster: fix stack-out-of-bounds read in

usb_check_int_endpoints by null-terminating array

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=UTF-8

Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit

Signed-off-by: Túlio Fernandes <tulio@localhost.localdomain>

---

drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c | 2 +-

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

diff --git a/drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c b/drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c

index 6c3e758bbb09..3b81468a1df2 100644

--- a/drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c

+++ b/drivers/hid/hid-thrustmaster.c

@@ -171,7 +171,7 @@ static void thrustmaster_interrupts(struct hid_device *hdev)

b_ep = ep->desc.bEndpointAddress;

/* Are the expected endpoints present? */

- u8 ep_addr[1] = {b_ep};

+ u8 ep_addr[2] = {b_ep, 0};

if (!usb_check_int_endpoints(usbif, ep_addr)) {

hid_err(hdev, "Unexpected non-int endpoint\n");

--

2.48.1

Then, using the git send-mail utility, I sent the patch to the maintainers responsible for the modified file. You can easily find their email addresses using the scripts/get_maintainer.pl script.

2. Lore

You can follow the entire discussion regarding this submission via this link on Kernel Lore. Lore is a public mailing list archive on the official Linux kernel website where everyone can follow the discussion, provide feedback, and gain insights into the contribution process. There, you will also find the commit details, including its title and a detailed description.

3. Review and acceptance

On February 7th, my patch was merged into the HID tree by its maintainer, Jiří Kosina (SUSE Labs). Then, on February 17th, the patch was submitted for review by Sasha Levin (NVidia) for inclusion in the stable/LTS branch—designed for long-term support—and, around the same time, Greg Kroah-Hartman (The Linux Foundation) submitted it for the 6.1-stable branch, which is the next version-specific stable tree.

In summary, the 6.1-stable branch (maintained by Greg Kroah-Hartman) receives new, thoroughly tested patches for upcoming releases, while the stable/LTS branch (managed by Sasha Levin) is for the next long-term supported kernel version.

Next steps

From this point forward, I plan to continue actively contributing to the Linux kernel, further expanding my knowledge and skills in low-level development. At the same time, I am looking to identify a kernel subsystem that truly captures my interest, so that I can dive deeper and specialize. I believe that with this focused approach, I can offer more significant contributions and keep a close eye on the evolutions and challenges in this field.

Final considerations

Reaching this milestone – my first contribution to the Linux kernel – fills me with a profound sense of accomplishment. Every step of this journey, including the setbacks and victories, has been a valuable learning experience, marked by persistence and passion. Reflecting on this achievement, I recognize it as one of the most significant goals I’ve reached in my IT life.

I also hope that my journey serves as an invitation to anyone who, out of fear or guilt, feels constrained from exploring new technical areas beyond their current expertise. If you have an interest or passion for a field outside your main area of work, know that dedicating time to broaden your horizons is not only possible but incredibly rewarding. Every small step is part of a much larger journey. Keep exploring, learning, challenging yourself, and enjoying the process—because the world of technology is vast and full of opportunities waiting to be discovered.

Thank you ; )